When gods from Hindu mythology appeared in the popular MOBA game SMITE, the Hindu American Foundation filed a complaint with the FCC. When Age of Mythology included Hindu deities as playable characters, cultural organizations protested the trivialization of sacred figures.

These incidents highlight a fundamental tension: game developers want to draw from rich mythological traditions, but when they directly copy religious figures, they risk cultural appropriation and community backlash.

This case study documents the development of AstraVerse, a framework for creating culturally-inspired game characters that are both novel and respectful. Rather than transplanting gods wholesale into games, AstraVerse enables designers to remix cultural elements systematically—creating original characters that honor traditions without copying sacred figures.

The Problem

God Transplantation

The common industry practice of directly copying religious figures into games creates ethical, creative, and business challenges. Sacred significance becomes secondary to gameplay mechanics.

Community Backlash

When gods like Kali or Ganesha appear in combat games, cultural communities react strongly—protests, FCC complaints, and boycotts follow misrepresentation of sacred figures.

The Designer's Dilemma

Avoid cultural themes entirely and miss creative opportunities? Or risk backlash by copying figures? Neither option serves games, players, or cultural communities.

Research Approach

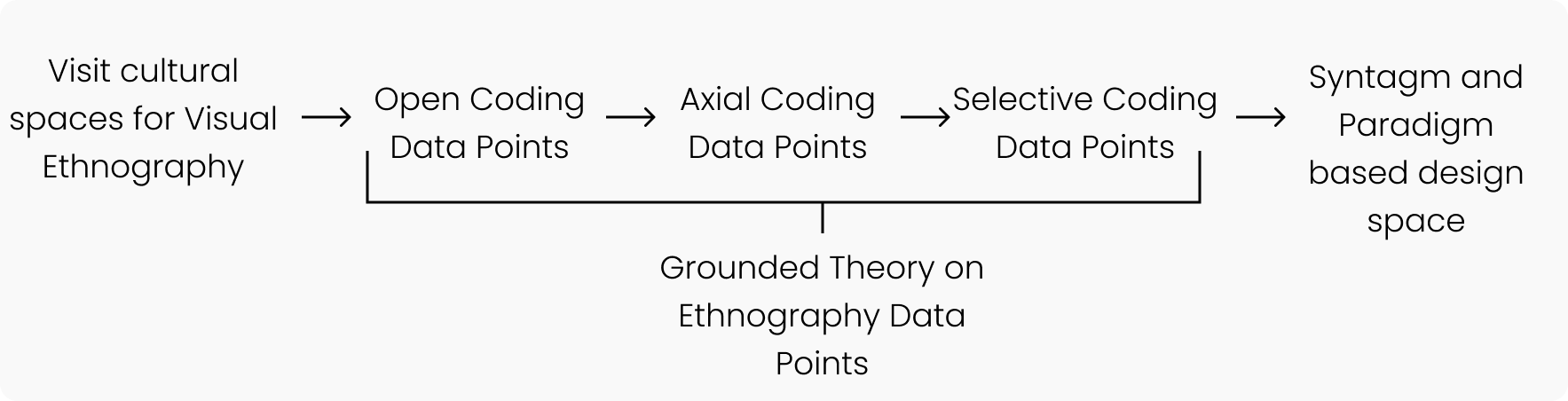

As Project Lead and Primary Researcher, I developed AstraVerse through a rigorous UX research process combining ethnography, design systems thinking, and participatory validation:

Visual Ethnography

Conducted fieldwork at 4 Hindu temples in California, collecting 429 cultural artifacts to understand authentic visual language.

Grounded Theory

Applied systematic analysis to identify 141 granular cultural elements (syntagms) organized into 22 categories (paradigms).

Card-Based Toolkit

Developed a design toolkit enabling designers to remix cultural elements like building blocks.

Designer Workshops

Validated through participatory workshops with game designers from UCSC's Game Design program.

Quantitative Analysis

Evaluated novelty using vector embeddings and statistical analysis across 141 dimensions.

Cultural Validation

Assessed sensitivity through interviews with Hindu temple priests and cultural experts.

.png)

Game designers participating in a design workshop using the card-based system.

Key Outcomes

The framework successfully balances creative freedom with cultural respect.

Visual Ethnography

To understand authentic cultural visual language—not stereotypes or Western representations—we conducted visual ethnography at four Hindu temples in Sunnyvale, California. This wasn't tourism; we systematically documented actual visual elements, rituals, and objects in these sacred spaces.

Over multiple visits, we collected 429 photographs systematically categorized:

- 248 Images of Idols: Sculptures showing canonical poses (mudras), clothing styles, ornaments, weapons, and symbolic attributes

- 63 Images of Rituals: Live ceremonies revealing contextual uses of objects, gestures, and spatial arrangements

- 45 Images of Objects: Ritual implements, ceremonial items, architectural elements, and symbolic objects

Collecting visual data from Hindu temples: idols, rituals, and cultural objects.

Understanding Cultural Stakeholder Concerns

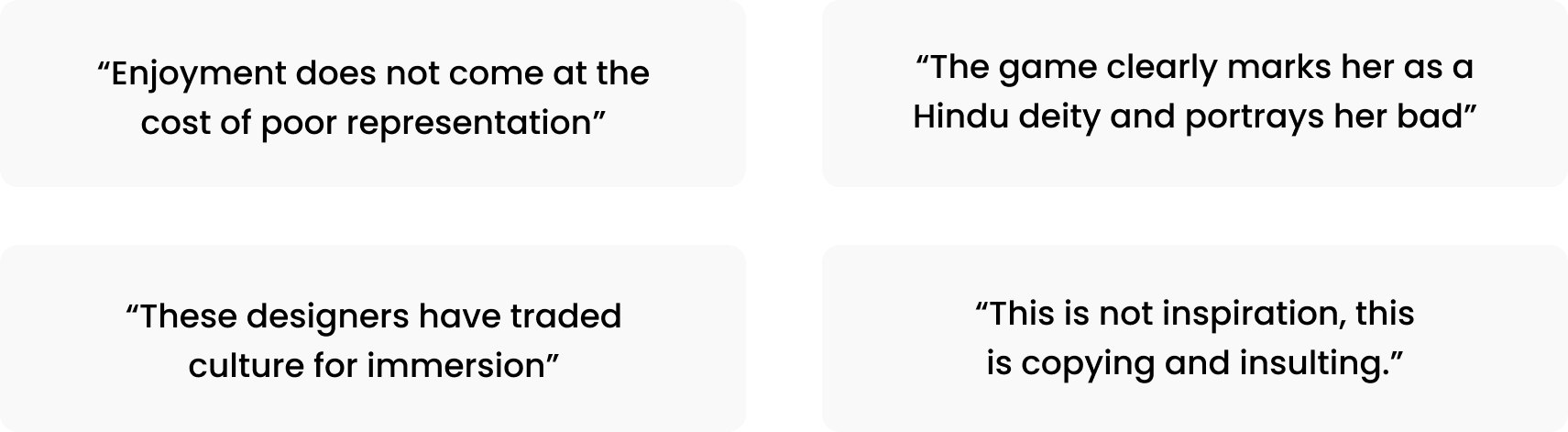

We showed temple priests examples of how Hindu gods appeared in existing games like SMITE and Age of Mythology. These conversations were critical for understanding what cultural appropriation actually looks like from the community's perspective.

Key concerns from cultural stakeholders: misrepresentation, trivialization, and manipulation of sacred narratives.

This insight shaped our framework: Rather than asking "How do we copy gods respectfully?", we asked "How do we create original characters inspired by cultural aesthetics?"

Building the Design System

The breakthrough: Rather than treating whole gods as units, we identified their component elements—ornaments, postures, symbolic attributes, color palettes. By making these elements modular and remixable, designers could create new combinations while staying culturally grounded.

From ethnographic data to a structured design space using Grounded Theory analysis.

The Final Design Space Structure

Granular, remixable elements—the "building blocks" (e.g., "trident with flames," "lotus mudra," "golden crown with peacock feather," "saffron-colored robes")

Thematic categories organizing syntagms (e.g., 'Headwear', 'Hand Gestures/Mudras', 'Handheld Objects', 'Mounts/Vehicles', 'Postures', 'Color Palettes', 'Symbolic Animals')

High-level conceptual pillars: Character Features (physical attributes, postures), Weapon Design (tools, weapons), Fashion (clothing, ornaments), Game Mechanics (symbolic associations)

The AstraVerse Toolkit

The framework was translated into a tangible design tool: cards representing identified cultural elements. Designers can search for specific elements similar to how Character Creation Interfaces in games present structured choices.

.png)

The AstraVerse card system: Paradigms structure the choice of granular Syntagm elements.

Validation

Three-pronged evaluation: usability, novelty, and cultural sensitivity.

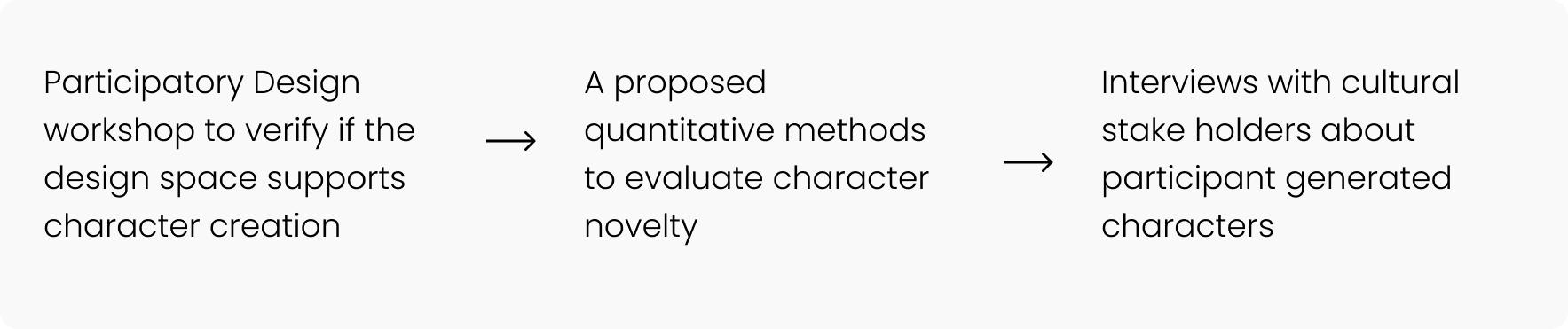

Participatory Design Workshop

We invited three game designers from UCSC's Game Design program to create two characters each using the toolkit, tasked with saving a fictional planet called "Vritra."

Intuitive & Engaging

Designers found the card-based system easy to navigate without training. The systematic structure facilitated more experimental combinations than free-form brainstorming.

Coherent Concepts

Designers consistently created characters with cohesive visual languages despite mixing diverse elements. "This gives me a starting point when I don't know what to design."

.png)

Designers actively using the toolkit in the participatory workshop.

Quantitative Novelty Analysis

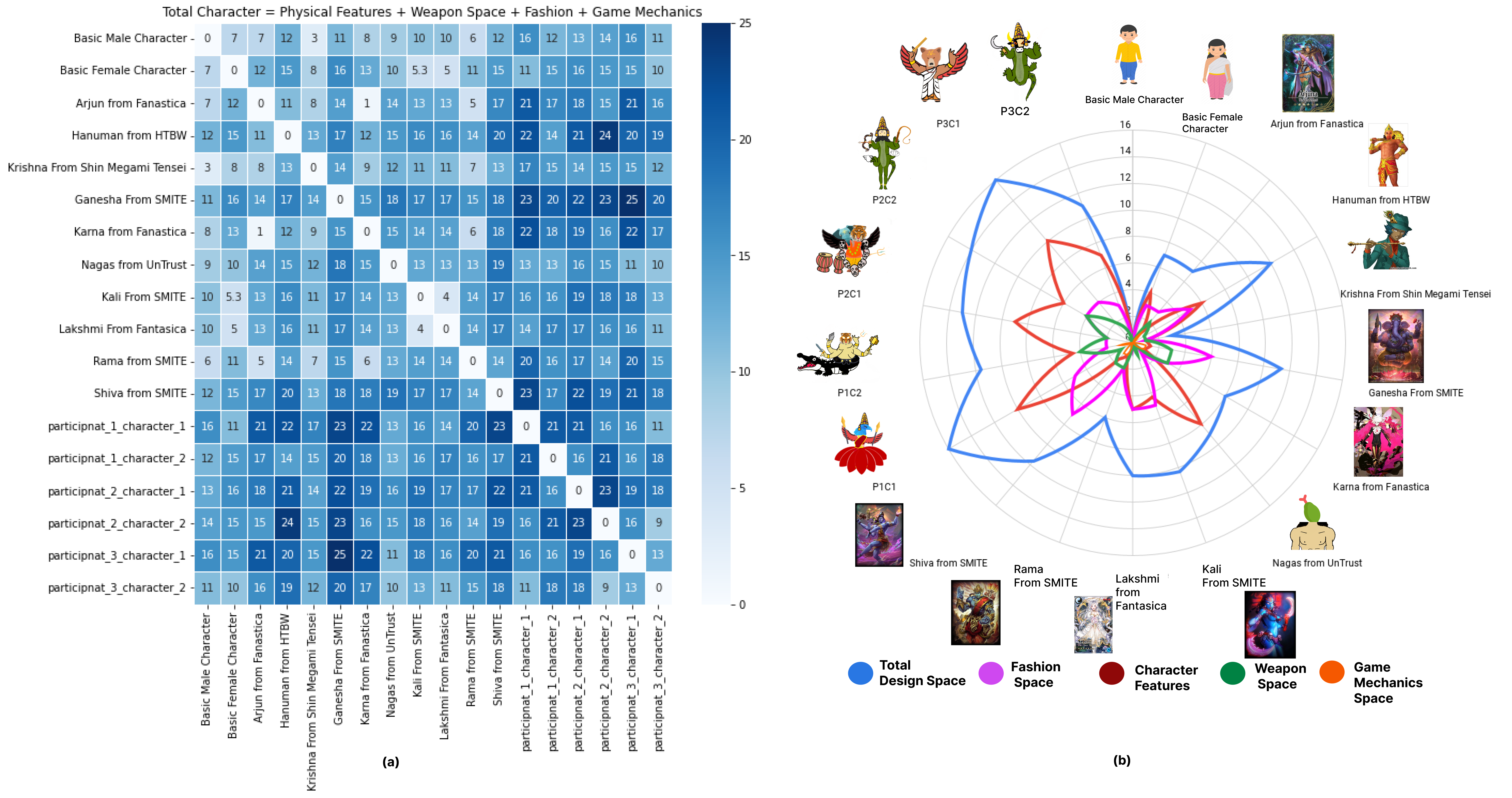

Each character was represented as a 141-dimensional vector based on syntagms. We calculated Canberra distance to measure novelty—comparing participant characters against all original Hindu gods from our data.

.png)

Every character represented as a vector across 141 dimensions.

Participant characters demonstrate clear distances from original gods across multiple dimensions.

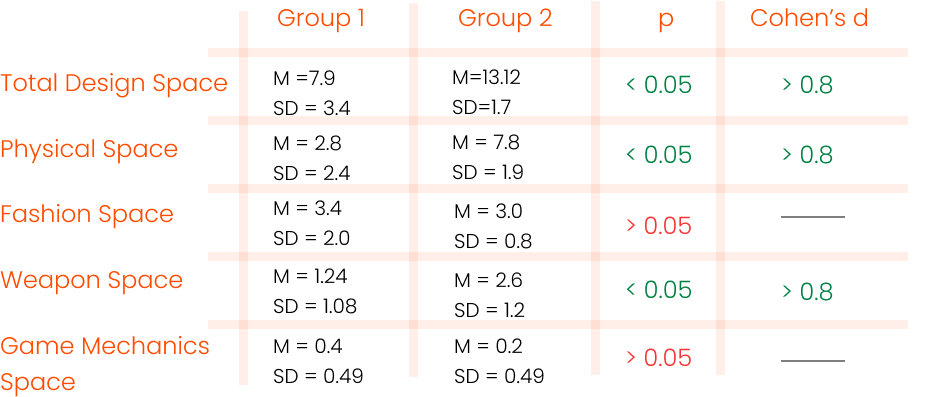

Statistical analysis confirming significant differences (p < 0.05, Cohen's d = 1.57).

Statistically Significant

Participant characters were distinct from copied gods across the entire design space (p < 0.05, Cohen's d = 1.57—a large effect size).

Comprehensive Novelty

Differences spanned multiple categories—Character Features (d = 1.8), Weapon Design (d = 1.1)—indicating comprehensive novelty, not minor variations.

Cultural Sensitivity Validation

Three cultural experts (two temple priests, one scriptural scholar) evaluated participant-generated characters alongside gods transplanted into games.

Positive Reception

Stakeholders recognized mythological elements but perceived generated characters as fictional creations inspired by—not copies of—mythology.

Creative Freedom

Cultural experts affirmed that creative liberty could be taken with narratives for these fictional characters, unlike for original sacred figures.

Conclusion

AstraVerse demonstrates that it's possible to move beyond direct appropriation in culturally inspired character design.

Through rigorous UX research and design, we created a system that provides designers with structured yet flexible tools for creative exploration grounded in cultural aesthetics.

The framework enables generation of characters perceived as statistically novel and visually unique, while producing concepts deemed culturally sensitive by cultural stakeholders. The methodology is replicable—applicable to other cultures and traditions seeking respectful creative engagement.

Skills & Methods Demonstrated

Visual Ethnography, Grounded Theory, Participatory Design, Statistical Analysis, Cultural Research

Game Design, Character Design, Design Systems, Framework Development, Workshop Facilitation

Qualitative Coding, Vector Embeddings, Novelty Assessment, Cultural Validation

Academic Publishing (FDG, ICEC), Cross-Cultural Design, Ethical Design Practice